The Smell Test

Writing with the Neglected Sense

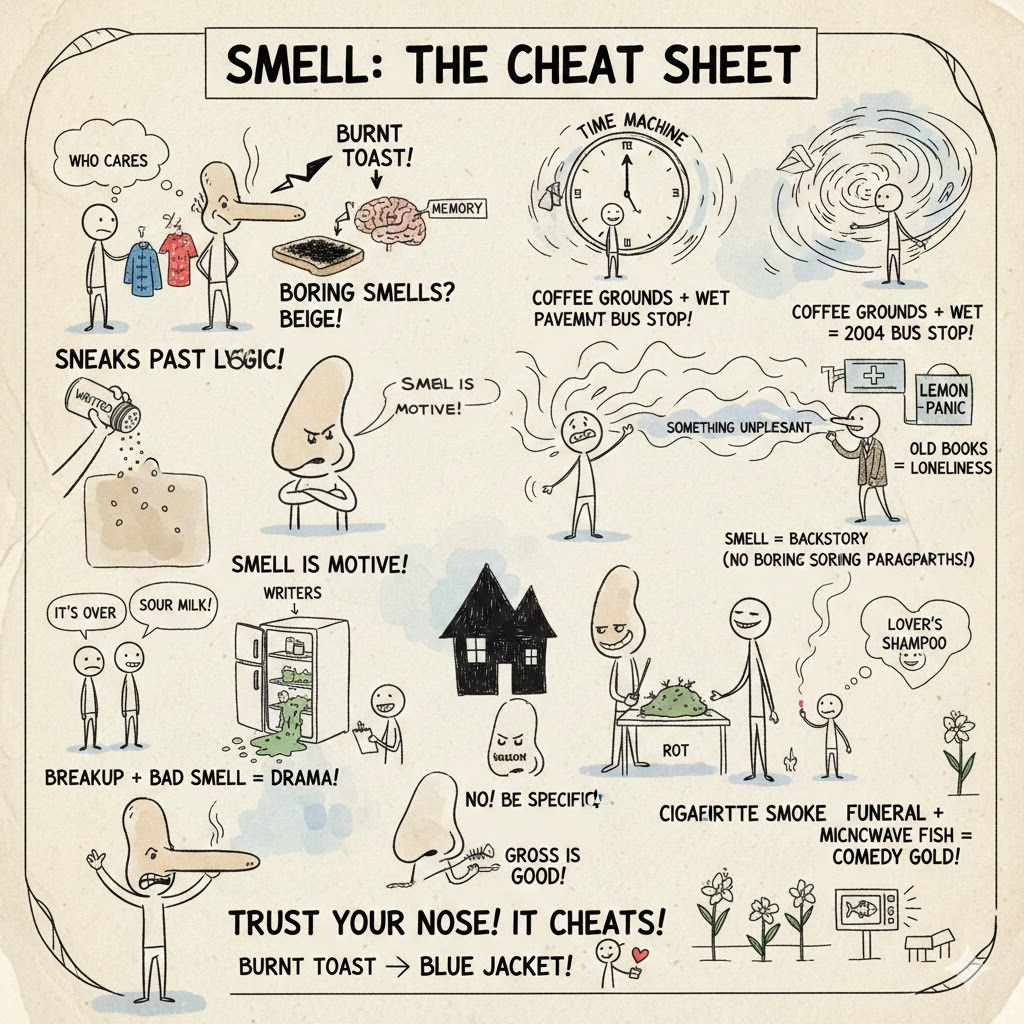

Readers will forget what your character wore. Blue jacket, red scarf, who cares. They’ll remember the smell of burnt toast. Because smell cheats. It sneaks past logic, past plot, straight into the nervous system. No ID check. No small talk.

Most writers sprinkle smell like they’re seasoning fries. Just enough to say they tried. Cinnamon. Fog. That vague weather-channel smell that means nothing and moves nothing. “The air smelled of rain.” Fine. Beige. Smell deserves better. Smell is not decoration. Smell is motive.

I learned this the dumb way. I once wrote a breakup scene that landed flat. Dialogue sharp, pacing tight, emotions labeled like jars. Still dead. In revision, I ditched a whole paragraph. One line replaced it. The place smelled like sour milk—the fridge dead, unplugged, days too late. After that, the scene finally did something. Suddenly the scene moved. Not because sour milk is poetic. Because it tells us something is wrong even before the people admit it.

Smell is a time machine with a cracked dial. You don’t control where it sends you. Coffee grounds on wet pavement—boom, a bus stop, 2004, your father late again. Hospitals smell like lemon cleaner and panic. Old books smell like dust and patience and a certain kind of loneliness that owns a cardigan.

Sight reports. Smell confesses.

When smell shows up in a scene, it carries memory on its back. That’s why it works as a narrative engine. You want backstory without a paragraph that sighs and sits down? Let the character smell something and flinch. Don’t explain it. Let the flinch do the work.

Smell also builds mood faster than adjectives ever will. “Dark” is a word. “The room smelled like damp socks and burned wires” is a warning. One says atmosphere. The other says get out.

And then there’s smell as a silent character. The thing that never speaks but keeps changing the room. Cigarette smoke that follows a father from room to room. Incense that pretends to be calm while covering something rotting underneath. A lover’s shampoo that lingers after they’re gone, obnoxious, smug. Smell doesn’t argue. It just stays.

Here’s the trap: writers get polite with it. They go abstract. “A familiar smell.” No. Name it. Be specific. Be a little gross. Life is. The body notices first.

But don’t spray it everywhere. Smell works because it’s selective. Overuse it and the reader goes nose-blind. One or two sharp hits. Let them echo. Let the reader do the rest.

Try this exercise. Write a scene twice. First pass, ban smell. Second pass, cut three visual details and replace them with one olfactory one. Not perfume ads. Real stuff. Burnt oil. Cheap soap. Damp cardboard. Notice how the emotional temperature shifts without you pushing it.

Smell also lies. That’s fun. Lavender to hide mold. Cologne to cover fear. A bakery smell pumped into a grocery store to make you hungry and stupid. Use that. Let smell mislead the reader the way it misleads people.

And yes, it can be funny. A funeral that smells like overripe lilies and someone’s microwave fish from the office next door. Comedy loves smell because it’s undignified. Bodies are. Writing should remember that sometimes.

I’m not saying every story needs a nose. I’m saying if your scenes feel thin, run the smell test. Close your eyes. If nothing hits you, maybe the scene isn’t alive yet.

Readers don’t remember outfits. They remember burnt toast. They remember gasoline on summer skin. They remember the way a room smelled right before something went wrong.

That’s not fancy craft talk. That’s just how humans work. Smell gets there first. Let it.

Absolutely! Tapping into smell gives a flat scene a 3D life. I used to give my writing students an exercise: describe a smell without saying the subject smells of something else. It is harder than it sounds!

I've spent plenty of time getting the taste of food right -- now I need to go back and add a few aromas. I can also think of a scene which would benefit from the smell of greasepaint and face powder. And I’m worried that it never occurred to me that many of the women would be wearing scent.